Referencing is one of the most important skills in academic and legal writing, yet it is also one of the most misunderstood. Many students see citations as tedious and hyper-technical.

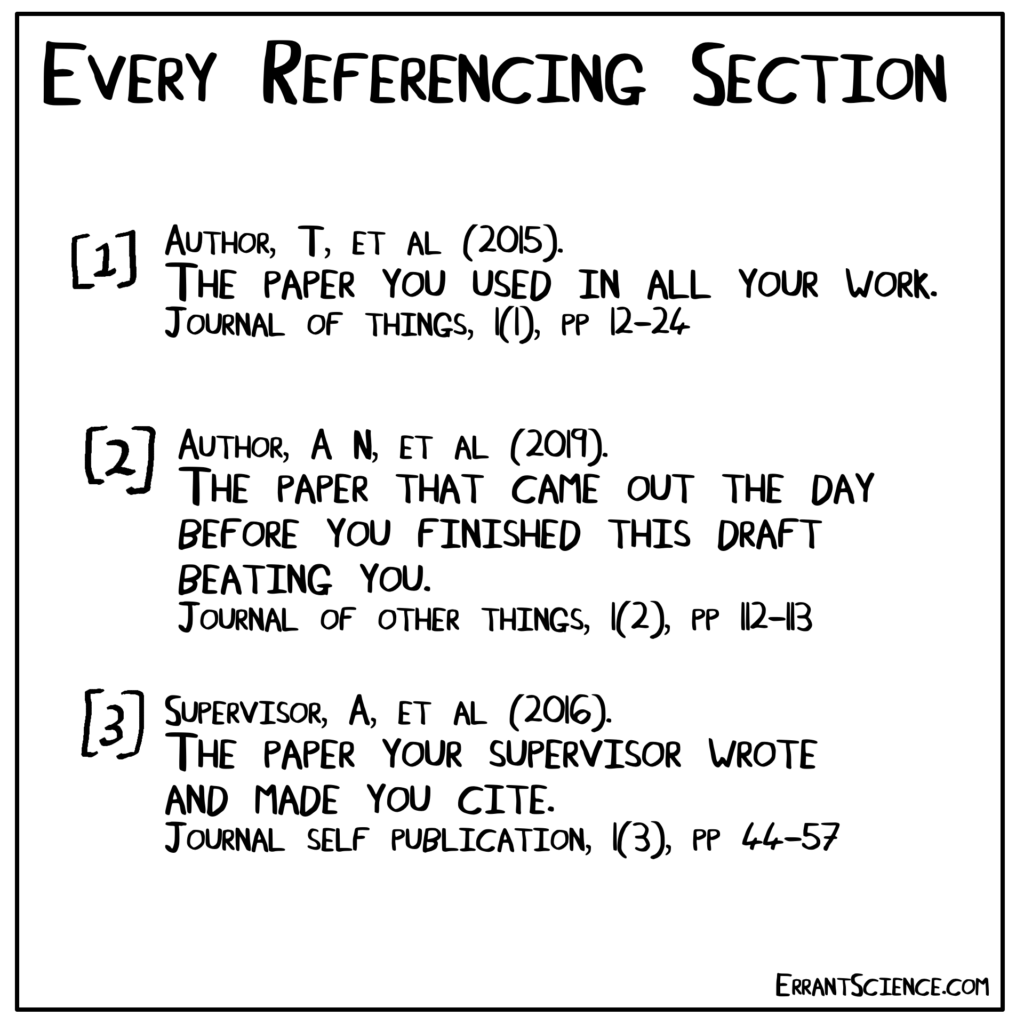

While hunting for an author’s first name or a publisher’s city, thoughts like “If only I was spending this time on the actual research” or “Will anyone notice if I skip this citation” often appear. But referencing is far more meaningful than a mechanical formality. It is central to how knowledge grows and how writers stay accountable within a community of learners.

The creation of knowledge is a community exercise. When we research, we build our ideas on the existing body of work developed in that field. In turn, we publish our work with the hope that others will read and make use of our research to tackle critical problems.

We need a system to acknowledge those who created something that made us want to engage with them. Referencing does precisely this. It helps us recognise scholars, writers and researchers whose work influenced our own. Whether you see it as a rule or as a well-deserved thank you, ideas that you draw or extrapolate from others must be properly cited.

This guide simplifies the what and why of referencing, explains when to cite and when not to cite, and helps you understand plagiarism. The aim is to make the process less intimidating and more meaningful.

Why Referencing Matters

Building Credibility

References show the foundation of your ideas. They demonstrate that your argument comes from research, reading and engagement with existing scholarship.

Helping Readers Navigate

A good citation trail acts like a roadmap. Readers can follow your references to explore the ideas that shaped your work.

Protecting Against Plagiarism

Plagiarism has serious consequences. Proper referencing ensures that you give credit to the original authors and protect your academic integrity.

Improving the Quality of Writing

With references, you can introduce contrasting views, add nuance, place additional details outside the main text and create a layered, well-informed manuscript.

Knowing What to Cite

The thumb rule is simple. Anything that did not originate with you but helped you support your writing should be cited. If referencing is about acknowledging intellectual debts, then you cite everything that helped you arrive at your argument.

What Needs to Be Cited

Use citations for:

- Words, quotations and phrases.

- Thoughts, ideas and opinions including their paraphrased versions.

- Numbers, statistics and data.

- Audio and visual content such as photos, videos, screengrabs, PowerPoint slides and social media content.

High quality sources include peer reviewed articles, credible academic books, government reports and publications by reputable institutions.

References Beyond Sources

Citations can do more than just acknowledge information.

You can insert additional text that you do not want in the main body. These may include definitions, tangential arguments, caveats or contrary viewpoints.

You can interlink parts of your own writing. This is especially useful for long documents. For example, if you introduce a concept early on and explain it in detail later, a footnote can guide readers to the relevant section.

Using references well can make your manuscript more organised and easier to follow.

What Not to Cite

Your Own Insights

Your conclusions, lived experiences and unique interpretations do not need citations because they are your original contribution.

Common Knowledge

Information that is widely known or easily verifiable does not require a reference. For example, the Earth revolves around the Sun. However, what counts as common knowledge depends on your audience.

Unreliable Sources

Magazines, personal blogs, unverified internet sources and online forums should be used with caution. Wikipedia should not be cited directly because its content is collaborative and constantly changing. It is useful only for preliminary understanding.

When in Doubt

If you are unsure whether to cite something, cite it. You will never be penalised for adding an extra citation, but skipping one can lead to plagiarism.

Avoiding Plagiarism

Academic referencing requires us to provide full bibliographic information so readers can trace the material. Failing to do so leads to plagiarism. Plagiarism is copying, stealing or passing off someone else’s work as your own. It involves drawing thoughts, ideas or opinions from a source without giving due credit. Plagiarism applies not only to published works but also to websites or material without clear authorship.

Types of Plagiarism

Direct Plagiarism

Copying text word for word without acknowledgment is the most obvious form. This includes copying someone’s style of writing and structure.

How to avoid it:

- Use quotation marks when lifting text.

- Cite the source properly.

- Paraphrase only when you can genuinely rewrite the idea in your own words while adding a citation.

Mosaic Plagiarism

The Oxford Learner’s Dictionary defines a mosaic as a picture made by placing together small pieces. Similarly, mosaic plagiarism refers to mixing words or phrases from another person’s writing into your manuscript without proper credit. Howard defines it as copying from a source text and then deleting words, altering grammatical structures or using one-for-one synonyms.

How to avoid it:

- Use quotation marks for borrowed phrases.

- Paraphrase meaningfully and cite the source.

Self-Plagiarism

Self-plagiarism or auto-plagiarism occurs when the author reuses their own published work without citation. Submitting the same research to multiple publishers is known as duplicate publication. Since you may have transferred copyright to the publisher, this can even cause copyright issues.

How to avoid it:

- Cite your previous work just like you cite others.

- Do not recycle past assignments or papers without attribution.

Accidental Plagiarism

This happens when a writer forgets to cite or unintentionally paraphrases too closely. Intent does not matter. Even accidental plagiarism counts as academic misconduct.

How to avoid it:

- Maintain organised records of your sources.

- Review your work carefully before submitting.

- Use plagiarism software to detect overlaps.

- Ensure quotation marks and footnotes are accurate.

Consequences of Plagiarism

Plagiarism invites serious consequences. These include rejection of your manuscript, disciplinary action by your university, loss of academic reputation and damage to future professional prospects. Although plagiarism is not a crime in India, it may still attract liability under sections 57, 63 and 63(a) of the Indian Copyright Act, 1957.

The University Grants Commission has notified the 2018 Regulations to promote academic integrity and prevent plagiarism in Higher Educational Institutions.

As a serious researcher, you must maintain intellectual honesty. This does not mean your work must always be original or unprecedented. It simply means producing work ethically, transparently and responsibly as you continue developing your own voice.